CHAPTER

In April the bombs started falling. Maureen's stomach started to hurt as she looked at the picture on the front page of the newspaper, black smoke pouring out of a bright orange fire, against the dusky sky. It resembled some kind of post-apocalyptic impressionist fresco, perhaps recalling some long ago battle. It was a stunning, horrible photograph that she couldn't take her eyes off.

For once, Maureen didn't know how she should feel. Politics usually seemed pretty clear cut to her. Meeting violence with violence only bred more. Everyone she had ever admired said so. Gandhi, Jesus, Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King. It was a principle worth taking even to the grave, refusing to take up arms, to take a single human life, no matter how viciously it was being lived.

She'd seen the photos of mass graves, reminiscent of those she had seen in history texts from fifty years ago. She remembered a story in Ms. Magazine, which told of an ethnic woman and her husband--Maureen couldn't remember if they were moslem or Croat--who had been captured by Serbian troops. The man had to watch as his wife's pregnant belly was cut open and their child removed and murdered, while she bled to death. Mo's stomach muscles tightened just thinking about the excruciating pain that woman must have felt. Maureen felt like vomiting. She closed her eyes, hoping to meditate on peace, believing that adding a little good energy to the world couldn't hurt, even if it wouldn't accomplish anything tangible. But all she could see was a large pregnant belly, open and bleeding like some kind of a horrible cocoon, with a woman's screams and gunfire and a weeping husband as the soundtrack. She frantically dug around in her backpack for her radio and headphones.

CHAPTER: CALLING HOME

Maureen's father talked with an accusation in his voice. Why are you doing that sounded to her seventeen year old ears like an inquisition, not a search or request for facts and it was consequently returned with what the hell business is it of yours followed by deep remorse hours and years later as she wondered how she could have been so mean to her own father who liked nothing so much as to tease or crack a joke, even if his humor found its mark on a too-fragile adolescent ego or on her mother's rage and insecurity and years later when she tried to remember when she and her father had quit talking, had learned to become strangers, she found two main culprits.

The first showed up when she was thirteen and even though she was unprecocious and didn't know about set yet, she was awkward in my awareness of herself sexually. Maureen had come across an article on incest and the first time, it occurred to her that fathers were men and could even think of their daughters in "dirty" terms and even though her father was not like that, it made her feel strange just the same and then guilty for the estrangement. But a few years later, she became privvy to information about friends whose fathers and stepfathers were "like that".

The other shrift came when she started to respond agrily to the accusations she perceived in his voice. She blamed myself for both. She had begun to try, when talking to her father, to hear the words not the tones and sometimes to repair those chasms, but they had never had the full and deep honesty it would take to rebuild those bridges slat by slat and Maureen wasn't sure if she had the courage. So phone calls were times to laugh and share news about their lives and sometimes Maureen sat in her room, on the bus, in a cafe, hundreds of miles away and tears burned in her eyes not for lost years past, but for years not yet lost, not recoverable.

The operator came back on the phone and Maureen wiped each of her cheeks with the back of her hand. "Maureen" she had after the beep. After a few moments, she heard a click like a small door opening, like a priest pulling back the screen to face a new penitent. Only this conversation would not be anonymous. Her confessors knew who she was, if not the right dispensations to offer.

"Where are you?"

"Um. I'm not sure. I'm at a pay phone somewhere."

"Well, what's the area code?"

Maureen looked around on the phone. The number above the receiver was scratched out. "Don't know."

"Why do you always call collect? Don't you have a phone card?"

"Now you won't pay for my phone calls Mom?"

"I'm just saying. I bet you call your friends with your phone card. But if we want to talk to you, we have to pay for it."

"Yeah, whatever."

Maureen heard some mumbling in the background and the click of an extra phone being picked up. Her father's voice came on. "How are you doing? Are you ok?"

"Yeah, Dad, I'm fine."

"You ok for money?"

"Well, I'm starting to run a little low . . "

"I'll put some more in your account."

"No you won't!" her mother interjected. "If she wants to run around the country like this, I'm not paying for it anymore."

"What the hell does that mean, anymore? I've been living off my savings. Remember? Job--four years of college I worked and three years after. Don't act like I haven't

been paying my own way."

"Oh, is that what you call it? Paying your own way? Finding a daddy figure to support you these last three years so you can say you're independent?"

"Fuck you."

"Don't talk to your mother like that."

"Sorry."

Her father continued. "Why are you doing this? Why do you want to run around like a bum? You should just come home and get a job."

"I just . . . this is just something I want to do, Dad."

"Why?" There was the tone. "Most young women don't do things like that."

"I'm not most people."

"That's for sure," her mother snorted. "Well, you can just pay for this little excursion on your own, young lady." Maureen heard a click on the other end.

"Why are you doing this?" her father continued.

"Are you talking to me, or Mom?"

He chuckled. "I know why she's doing this. I just don't understand you. This whole thing with your professor, and now this trip thing. What are you going to do with yourself?"

"I don't know, Dad. I don't need money. I'm going to stop somewhere pretty soon and get a job."

"What kind of job?"

"I don't know. Temping, maybe. I've got good computer skills. Maybe something in a little bookstore."

"That's what we sent you to college for? To work in a bookstore? To type in an office all day? Do you even have any work clothes with you? How are you going to go to an interview."

"Look," Maureen tried hard to keep her voice measured. Don't get annoyed. He's just asking you an innocent question. "I'll work it out, ok?"

"Did he do something to you? Did he beat you up? Did he have an affair? Did he run off with one of his new students?"

"Dad!"

"You can't go around running away from things. You can't just turn yourself off and

go disappear."

"I just needed to get away. Look, just because I'm not around everyone, being melancholy doesn't mean I'm running away. You don't know me anymore. I've been gone for seven years now."

"We miss you. How long can you do this? Eventually, you're going to have to stop somewhere and settle down. Don't you get sore from sitting on that cramped little bus all the time?"

"Well, sometimes. But then I get off for a while. I go look around, stay overnight when I can afford it sleep in the park during the day." Maureen was sorry as soon as the words left her mouth.

"You sleep in the park? That's just great. When people ask me what my daughter does, I can tell them she's indigent."

"I'm not sure I'm ready to come back. I mean, yeah I'm a little lonely. I miss Clark. But this is important."

"How? What is so important about this? I want to know how you think you're saving the world running around on a Greyhound and sleeping the park"

"By finding out about it, Dad."

"Then what?"

"I don't yet. I haven't thought that far ahead."

"See, that's what I mean. You have to start thinking about things. About things other than what you want right this minute. The world's not like that,Mo."

"Look, I gotta go. I think someone else wants to use the phone." Maureen looked across the empty parking lot.

"I'll put a little money in your account. Pay it back someday. When you get a life, ok?"

"Whatever. I don't need it Dad . . . "

"You're mother and I love you. Stay safe. I don't want to come identify your body in Nebraska or wherever you are. Ok? Just be careful."

"Bye."

Maureen hung up the phone. She noticed a large old car, some kind of old cadillac or LTD circling the parking lot. Maybe they just wanted to use the phone, she told herself. But she was too spent to take any chances. She cursed her stupidity for picking a pay phone in the middle of a big, open, empty parking lot on a Sunday morning. She stepped down the curb onto another piece of pavement, and the car sped around and entered the other lot. She clutched her backpack to her and trying not to look like she was noticing them, walked faster toward the sidewalk . If she could just get to the street, which was busy enough for people to notice her, maybe the driver(s) of the car would give up on her. She thought she had seen two people in the car, but didn't want to look too closely, for fear of encouraging their company.

Maureen walked faster, listening to the car heading towards her. Her cheeks felt hot. Stay safe. We miss you. She started to cry and broke out into a run toward the intersection. A car slammed on its brakes to her left. "Watch where the hell you're going. What are you trying to do, get killed?"

She stepped backwards onto the curb and watched her pursuer(s) drive off. Shaking, Maureen set her bag down on the grass and sat on top of it, running her hands through her scalp and crying, watching pictures of her father and her mother identifying her body.

Thinking of her mother always made Maureen think of sadness.. And then guilt.

No one over sixteen wants to be thought of as a tragic case. But in her mother, she couldn’t help but see loneliness. Despite their worry, Maureen saw her own life as happy and independent life. Suddenly, Mo’s mother had develed what seemed to her a newer dependence on her, a new need for family, as if through Mo, she could either repeat or redeem her separation from her own mother. Maureen felt her own indaequacy as a daughter, worried and guilty about leaving her completely alone to fend for herself.

When Maureen imagined her mother the young woman, she saw dreams deferred--a small, slightly older version of myself, wringing her hands and trying not to cry at airport terminals. Trying. Trying so hard.

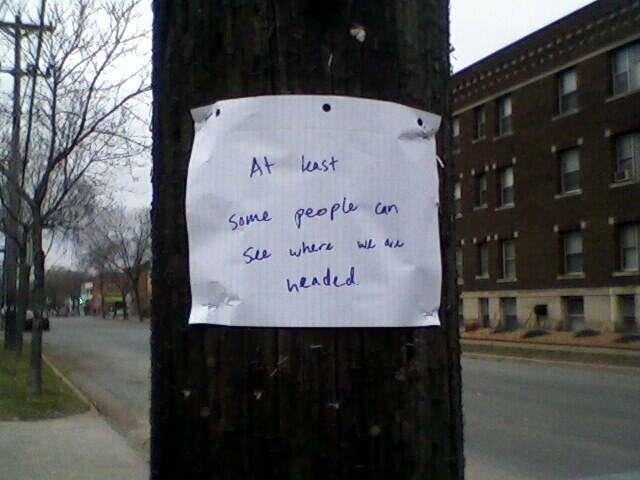

Surrealist Doodle

This was used as the cover of Karawane in 2006 and I have included it in on a number of bags and postcards over the years. Someone on the subway asked me if it was a Miro. I was very flattered!

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Wednesday, April 17, 2013

Chapter 11 of my accursed novel

CHAPTER: CLARK

With spring came the bombing of Kosovo. Clark found himself in the odd position of supporting a US military action. He could not find a single point of self-interest for the United States. There was no oil. The country was devestated from war. There might be economic gains in the future during the country's rebuilding, and yet we were bombing the Serbs--a group of white European background, who appeared to be emerging as the victors, the group that multinational corporations would someday want to court to locate manufacturing plants and sell soft drinks to the country.

For at least five years, if not more, the world had watched pictures of tremendous brutality. Stories of the rape camps, were moslem and croatian women were used as sexual objects. He had read articles and stories where the Serbian army had taught the rank and file to talk about their "enemies" as not human. And they seemed to believe it. Milosevic had been convicted of war crimes and atrocities several times. For the past twenty years, every skirmish was justified by painting our targets as purely evil. Saddam is just like Hitler. Noriega is oppressing his people and shipping drugs to the US. And yet, here was the closest justifiable comparison to Hitler --a leader with no regard for the human suffering of his opponents; a force that used phrases like "ethnic cleansing" to justify genocide--and yet no one was willing to stand up to him. For once, Clark felt shocked at the level of dissent against the bombing.

Yet Clark was not able to feel good about adding to an already devastated country. The picture on the front page of the newspaper looked more like painting, eerie greys and blacks, with a colorful dash of orange at the epicenter. As he watched the wall-to-wall coverage on cable tv, he thought maybe twenty-four hour news was a bad thing, commodifying what was a very serious situation. "The Bombing in Kosovo: Day 2". It came complete with quizzes about where the Mig fighters were being dispatched from and "the answer after this."

Clark decided to take a walk by the federal building and see if there was anyone there he knew. Or, more accurately, anyone there Maureen knew, as he suspected students were much more apt to be there than any of his colleagues. Arrests looked bad at tenure hearings. As he walked by a group of protestors, he heard someone shouting about how they were Serbian and they were worried about their families. Funny, in all this time, he hadn't heard anything about a large pocket of Serbian refugees living in the area. He walked up and began trying to talk to one of the protestors. He tried to calm himself down first. Feeling the blood rush to his face, he knew that it would do no good to be confrontational.

"So, if you're Serbian, how do you feel about what your people have been doing over there until now?"

"Not my family. It's not my fault what the army has done. It's not fair to kill innocent people like this."

"But, what about the innocent Moslems or Croats, or . . . Albanians."

"It is our country now. We need to have our own country. They can go back to their own countries."

"Then what are you doing here?"

"How dare you."

"No, I'm quite serious. If your country is so wonderful, go and defend it. You know, as an American, all I've done most of my life is apologize for my country and try to get them to stop doing what they were doing. Don't support the Shah of Iran, lift sanctions against Cuba, don't bomb Iraq. Blah blah blah. What have you been doing to prevent this bombing from being necessary?"

"Fuck you."

"I'm just saying, I've never seen you out here before to protest atrocities against the moslems, against people you probably grew up with. If your homeland is so right, why are you here looking for political asylum and not over there, defending your family and fighting for your cause."

A young blond woman came over, placard in hand, and starting shouting at Clark.

"It's a free country. We can stand here and protest whatever we want. What are you, some kind of a right-wing asshole? You think everyone should just go back where they came from so we can bomb them?"

"Look, little girl, before yesterday, did you even know where Kosovo was? Can you even pronounce Milosevic? Do you know a Serb from a Croat?"

The young woman started to clap and yell, and soon a chant had begun to swell among the crowd, drowning out any further opportunity for discourse. At least, thankfully, this was an anti-war protest, and so most of the crowd advocated nonviolence. At previous rallies, Clark mused, he was up against pro-war demonstraters, who had no problem with violence whatsoever. He shook his head, shoved his hands in his pockets, and wandered off. What a strange thing, to be defending a military intervention. And yet, despite such a shifting of the world, he thought, we still hadn't learned to talk to each other.

Clark had always had a sympathy toward eastern religions. Reincarnation had seemed to make perfect sense to him. After all, how fair can it be that with somewhere between one and 105 years, your entire eternity would be determined. And didn't premature death leave the playing field very unlevel. Sure, if everyone died at birth, everyone could go to heaven. Unless you were Catholic and unbaptized prior to Vatican II, and then you had to go to Limbo. And even though no one ever talked about those old nature vs. nurture debates, science was still trying to prove that everything about our personalities was chemical and determined by DNA and electrical impulses. It seemed just as plausible that your DNA imprint, your personality, was simply your Karma travelling with you. Why do two people, with identical backgrounds, do drastically different things. Why does one child who is abused grow up to become a rapist and a murder while another becomes a social worker? It was simply your Karmic imprint, continuing your personality and temperment from your previous life.

Yet, reincarnation seemed to carry with it a notion of progression. As Clark looked around him, though, he couldn't buy that anymore. He looked at the people on the bus, in the booths at the coffee shop, beating on their kids or talking about some inane bullshit like their car payments or what Elizabeth Taylor wore to the Oscars, or how they spent six hours a day mastering a new video game. He wanted to jump up and yell "You're going to die someday, and what will you have to show for your lives?"

Society at large didn't bear up too much better under the notion of human progression. We were still executing people for crimes, ridiculously schizophrenic over sex--both obsessed with it and shamed and embarrassed by it--and we hadn't found a way to deal with our neighbors on a civilized human level. No, if reincarnation was going to work as any kind of a believable doctrine, we were going to have to let go of the notion of karmic progression. Maybe, instead, one ran around in circles for a long time, like a dog chasing his tail. Each lifetime, there was something new and interesting attached to your tail that you tried to chase--money, sex, power. Only then, only when you had tired completely of everything life had to offer, only then did you actually advance to a higher level. So even though learning might happen between lifetimes, it merely propelled you on to the next thing, not onto a higher level.

Once, as a graduate student, Clark remembered grading a paper in which a student was writing about Siddhartha. He read a sentence that sent him off on a spiritual reverie: "Because Siddhartha still had desires, he would have to be reborn." Of course! Years of gurus had not been able to make eastern religion as accessible to him as this college freshman had--probably inadvertently, grasping for a way to explain a concept very foreign to him. Yes, it was not that you had to transcend your desires, but that you needed to experience them, get them out of your system, before you could get to nirvana.

It's sad to think we'll never exist on this plane, as ourselves again. Death is not only letting go of life. It is letting go of people, of thoughts and words and your soul ordered in a certain way. It's like losing your spiritual DNA, the collection of molecules and biological memory. It's leaving behind people who will forget you, who will be forgotten, and love and friendship and fun and words you thought you'd carved into their hearts, that you meant to write on the sky in indelible ink, that you carved into the trees and onto the sides of mountains like billboards proclaiming that you were here only to see them washed away, eroded for the next generation. The generation that will not mark the day you were here. Or the day you left. Or any of your days in between.

You have to content yourself with a silent legacy, with anonymity in every word you left behind, every thought you shared with every other person. Ancient artisans left no identifying mark on their work. Pick up a vase, or a plate or a ceremonial bowl, and you will never know who made it. Copyright a poem, patent a sheep clone, but nothing leaves my mark on the world. A silent invisible legacy that hoped for something large, something immortal, and left only ephemera.

With spring came the bombing of Kosovo. Clark found himself in the odd position of supporting a US military action. He could not find a single point of self-interest for the United States. There was no oil. The country was devestated from war. There might be economic gains in the future during the country's rebuilding, and yet we were bombing the Serbs--a group of white European background, who appeared to be emerging as the victors, the group that multinational corporations would someday want to court to locate manufacturing plants and sell soft drinks to the country.

For at least five years, if not more, the world had watched pictures of tremendous brutality. Stories of the rape camps, were moslem and croatian women were used as sexual objects. He had read articles and stories where the Serbian army had taught the rank and file to talk about their "enemies" as not human. And they seemed to believe it. Milosevic had been convicted of war crimes and atrocities several times. For the past twenty years, every skirmish was justified by painting our targets as purely evil. Saddam is just like Hitler. Noriega is oppressing his people and shipping drugs to the US. And yet, here was the closest justifiable comparison to Hitler --a leader with no regard for the human suffering of his opponents; a force that used phrases like "ethnic cleansing" to justify genocide--and yet no one was willing to stand up to him. For once, Clark felt shocked at the level of dissent against the bombing.

Yet Clark was not able to feel good about adding to an already devastated country. The picture on the front page of the newspaper looked more like painting, eerie greys and blacks, with a colorful dash of orange at the epicenter. As he watched the wall-to-wall coverage on cable tv, he thought maybe twenty-four hour news was a bad thing, commodifying what was a very serious situation. "The Bombing in Kosovo: Day 2". It came complete with quizzes about where the Mig fighters were being dispatched from and "the answer after this."

Clark decided to take a walk by the federal building and see if there was anyone there he knew. Or, more accurately, anyone there Maureen knew, as he suspected students were much more apt to be there than any of his colleagues. Arrests looked bad at tenure hearings. As he walked by a group of protestors, he heard someone shouting about how they were Serbian and they were worried about their families. Funny, in all this time, he hadn't heard anything about a large pocket of Serbian refugees living in the area. He walked up and began trying to talk to one of the protestors. He tried to calm himself down first. Feeling the blood rush to his face, he knew that it would do no good to be confrontational.

"So, if you're Serbian, how do you feel about what your people have been doing over there until now?"

"Not my family. It's not my fault what the army has done. It's not fair to kill innocent people like this."

"But, what about the innocent Moslems or Croats, or . . . Albanians."

"It is our country now. We need to have our own country. They can go back to their own countries."

"Then what are you doing here?"

"How dare you."

"No, I'm quite serious. If your country is so wonderful, go and defend it. You know, as an American, all I've done most of my life is apologize for my country and try to get them to stop doing what they were doing. Don't support the Shah of Iran, lift sanctions against Cuba, don't bomb Iraq. Blah blah blah. What have you been doing to prevent this bombing from being necessary?"

"Fuck you."

"I'm just saying, I've never seen you out here before to protest atrocities against the moslems, against people you probably grew up with. If your homeland is so right, why are you here looking for political asylum and not over there, defending your family and fighting for your cause."

A young blond woman came over, placard in hand, and starting shouting at Clark.

"It's a free country. We can stand here and protest whatever we want. What are you, some kind of a right-wing asshole? You think everyone should just go back where they came from so we can bomb them?"

"Look, little girl, before yesterday, did you even know where Kosovo was? Can you even pronounce Milosevic? Do you know a Serb from a Croat?"

The young woman started to clap and yell, and soon a chant had begun to swell among the crowd, drowning out any further opportunity for discourse. At least, thankfully, this was an anti-war protest, and so most of the crowd advocated nonviolence. At previous rallies, Clark mused, he was up against pro-war demonstraters, who had no problem with violence whatsoever. He shook his head, shoved his hands in his pockets, and wandered off. What a strange thing, to be defending a military intervention. And yet, despite such a shifting of the world, he thought, we still hadn't learned to talk to each other.

Clark had always had a sympathy toward eastern religions. Reincarnation had seemed to make perfect sense to him. After all, how fair can it be that with somewhere between one and 105 years, your entire eternity would be determined. And didn't premature death leave the playing field very unlevel. Sure, if everyone died at birth, everyone could go to heaven. Unless you were Catholic and unbaptized prior to Vatican II, and then you had to go to Limbo. And even though no one ever talked about those old nature vs. nurture debates, science was still trying to prove that everything about our personalities was chemical and determined by DNA and electrical impulses. It seemed just as plausible that your DNA imprint, your personality, was simply your Karma travelling with you. Why do two people, with identical backgrounds, do drastically different things. Why does one child who is abused grow up to become a rapist and a murder while another becomes a social worker? It was simply your Karmic imprint, continuing your personality and temperment from your previous life.

Yet, reincarnation seemed to carry with it a notion of progression. As Clark looked around him, though, he couldn't buy that anymore. He looked at the people on the bus, in the booths at the coffee shop, beating on their kids or talking about some inane bullshit like their car payments or what Elizabeth Taylor wore to the Oscars, or how they spent six hours a day mastering a new video game. He wanted to jump up and yell "You're going to die someday, and what will you have to show for your lives?"

Society at large didn't bear up too much better under the notion of human progression. We were still executing people for crimes, ridiculously schizophrenic over sex--both obsessed with it and shamed and embarrassed by it--and we hadn't found a way to deal with our neighbors on a civilized human level. No, if reincarnation was going to work as any kind of a believable doctrine, we were going to have to let go of the notion of karmic progression. Maybe, instead, one ran around in circles for a long time, like a dog chasing his tail. Each lifetime, there was something new and interesting attached to your tail that you tried to chase--money, sex, power. Only then, only when you had tired completely of everything life had to offer, only then did you actually advance to a higher level. So even though learning might happen between lifetimes, it merely propelled you on to the next thing, not onto a higher level.

Once, as a graduate student, Clark remembered grading a paper in which a student was writing about Siddhartha. He read a sentence that sent him off on a spiritual reverie: "Because Siddhartha still had desires, he would have to be reborn." Of course! Years of gurus had not been able to make eastern religion as accessible to him as this college freshman had--probably inadvertently, grasping for a way to explain a concept very foreign to him. Yes, it was not that you had to transcend your desires, but that you needed to experience them, get them out of your system, before you could get to nirvana.

It's sad to think we'll never exist on this plane, as ourselves again. Death is not only letting go of life. It is letting go of people, of thoughts and words and your soul ordered in a certain way. It's like losing your spiritual DNA, the collection of molecules and biological memory. It's leaving behind people who will forget you, who will be forgotten, and love and friendship and fun and words you thought you'd carved into their hearts, that you meant to write on the sky in indelible ink, that you carved into the trees and onto the sides of mountains like billboards proclaiming that you were here only to see them washed away, eroded for the next generation. The generation that will not mark the day you were here. Or the day you left. Or any of your days in between.

You have to content yourself with a silent legacy, with anonymity in every word you left behind, every thought you shared with every other person. Ancient artisans left no identifying mark on their work. Pick up a vase, or a plate or a ceremonial bowl, and you will never know who made it. Copyright a poem, patent a sheep clone, but nothing leaves my mark on the world. A silent invisible legacy that hoped for something large, something immortal, and left only ephemera.

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Chapter 10 of my accursed novel

CHAPTER: Chicago

Twenty years ago, she might have hitchhiked her way out of town instead. Stuck out her thumb in front of a kindly cross-country semi driver, or jammed with a van full of hippies. Maybe she'd be telling her story to a nice older couple who reminded her of her grandparents--a couple who would listen politely and later, after dropping her off, be grateful that their own grandchildren where married or in school right now, not traipsing around the country aimlessly. But she had answered too many late night crisis calls, made referrals for rape counselors and emergency room treatments, to place that kind of trust in the kindness of strangers.

Maureen surveyed the 2:30 a.m. bus station. A couple of guys her age plunked quarters into portable televisions for 15 minutes at a time. A group of young black guys were animately playing pinball, shaking & slamming the machine. A few children were scattered around the terminal, sprawled over rows of seats, sleeping oblivious to their dingy, uncomfortable accomodations.

She looked down at the floor. It was unmopped, but there were no visible signs of life there. Maureen dropped her backback down into a corner and lowered herself onto the floor. Cupping her head & arms around the backpack as a pillow, she closed her eyes and immediately fell into that middle place between sleeping and waking. She felt her breathing change and the sounds of pinball and television and waking, crying babies drifted a little further away. It turned into a wallpaper of sound. Black wallpaper with dancing flowers blinking duller and brighter with decreases and increases of noise. In front of the wallpaper, she dreamed where she had been. She walked through rooms of Clark's house that led downstairs in the shelter, where children ate breakfast before school as if they were in their own homes.

The wallpaper fell, rolling itself down the walls of classrooms where she had studied Spanish and history. Clark wrote notes the wallpaper in incandescent marker, moving quickly from panel to panel, top to bottom, to fill the entire room. She watched his lips form words taht she was forgetting to hear and all she wanted to do was jump out of her desk and run over to him, but he was so busy writing that he didn't know she was there. And then a voice came into the classroom over the loudspeaker announcing "Now boarding at door 7, the 3:15 for Chicago and all points east . . . ."

The wallpaper faded to gray and then white as Maureen forced her eyes open and looked up at the fluorescent light over her head. The bus room sounds rushed back to her and she saw a small line of people--the tv watchers and a couple of the pinball players, and a young mother with two children--all with their suitcases on the floor beside them, waiting to board the bus.

Still sleepy and disappointed, she sat upright and focused her eyes on the young woman. This small family might have passed through a shelter like the one Mo was leaving. Maybe this was a midnight run away from a battering husband. The family looked a little grungy. The woman's toddler daughter flopped limply over her shoulder while the son, maybe 7 or 8, leaded against his mother trying to catch--or not to lose--a few moments of standing shut-eye.

As Maureen stood up and grabbed her backpack, heading toward the short line, she hoped that the bus wasn't already too crowded. All she wanted was a seat to herself to stretch out, without the obligations of conversation, to sleep. And maybe to re-eneter the wallpapered classroom to see how her dream might have ended.

Maureen stretched out with a book, grateful that she wouldn’t have to share a seat with anyone. She was prepared to advise potential neighbors that she had a long trip ahead of her and would want to stretch out to sleep. , which was true, despite the fact that she had no set destination. After a couple of months on the road, she was beginning to view as interlopers anyone who would be on the bus less than four hours--dilettantes of the road. As a hearty cross-country traveler, she has surely earned some stripes. Her legs stretched across both seats causing her feet to jut slightly into the aisle, a large knapsack riding shotgun, and her nose seemingly buried in a book from which she peered up furtively as people passed her seat, new passengers would stop in front of her then begin scanning the rest of the bus for more welcoming accommodations.

Comfortably dug in, Maureen moaned as the bus driver stood up beside the front luggage rack and turned on the small television sets perched throughout the bus. He popped in a videotape, informing them tha their family-friendly distraction for the next two hours would be Pollyanna.

Maureen tried to focus on the text before--a storebought copy of Steal This Book. Abbie Hoffman was, ironically, advising junior outlaws on how to get free greyhound rides by various nefarious machinations, and Mo was kicking herself for shelling out her money to the authorities for her trek. Despite her anguish over the system, though she knew she was too ernest to pull off a scam straight-faced, she convinced herself that it was just as well. There were always too many revolutionaries in jail, many, she suspected, for foolish rather than meaningful breaches of the law.

She was not anxious to waste her time and her bail money in that manner.

The television continued to draw her attention away from the manifesto before her and she could not help from staring up, mesmerized as she was repulsed. One of her favorite things about life on the road had been the lack of distractions. She could listen in on people’s conversations if she liked or stare out the window in a reverie, contemplating the long corridors of trees like a receiving line, pine trees lifting their skirts in curtsey, ballerinas skinny string bean pine trees with bird legs, olive oyl in green fur coats and tutus. But she could just as easily sleep or read or just entertain her own thoughts. She especially loved the dark quiet overnight bus trips, with the occasional small overhead lights turned in here and there in the bus, as night owls quietly read or stared into the darkness trying to make out barns and silos. But the television demanded her senses engage like an angry parent screaming for a child to pay attention or a neglected lover trying to hold onto their allure. The television screen reached out to her jaw and tipped it back each time her independent mind tried to reassert itself.

Images of Big Brother imposed themselves over the young face of Halley Mills, Stalin in a ruffled yellow dress, his flat square social-realism index finger poking in her face and informing her that despite the insistence of MTv, the counterrevolution would be televised. On the streets of the cities loud music was constantly coming out of overhead speakers on the street and in Minneapolis, Mo remembered noticing video cameras perched from atop streetlight poles. As long as you are never alone with your thoughts, unable to entertain private ideas, you will never cast off your shackles. A chicken in every pot a car in every garage and a television in every room.

Maureen intermittently set her book in her lap, her finger inserted in the book to hold her place, and picked it up again, trying to reassert her attention span. Midway into the movie she began to wonder how the name Pollyanna had gained such a bad rap. Did people really loathe the cheerful little girl more than the complacent sourpusses under the thumb of an aristocratic tyrant? Was meanness and cowardice really preferable to optimism? the bumpy bus ride was also starting to make her horny and she felt slighly blasphemous to think of sex while watching Pollyanna. She tried once more to turn her face toward the window and avoid the halogen gaze of a child who no longer existed. If she couldn’t read or think, maybe she could at least catch a short nap and ream of what might be at her next destination.

Heading west from Chicago, they were informed that there would be a long lunch layover in the next small town. Maureen craned her neck to see the approaching road signs: Dixon, Illinois. Boyhood Home of Ronald Reagan.

It had been a couple of days since she had managed a full shower, although she took sponge baths each day in whatever restaurant or bus terminal washroom was available. She felt a bit grungy, but stopping in the gas station restroom to check herself in the mirror, determined that she was still presentable to go out looking for food. She stepped into a bathroom stall to change into the fresh dress she had brought from her backpack. It was a sleeveless knit dress that fit like a t-shirt, perfect for the warm June day, with a bright yellow sunburst amid a tie-dyed milkyway.

She tucked her shorts and tshirt into the smaller bag she carried with her on stops and headed down the street, looking for a place to while away the afternoon. She passed several fast food restaurants, but kept walking, as she preferred to frequent small, family-owned restaurants, thus supporting the local economy. She found a small diner that appeared to be the remnant of an A&W, with the long davenport covering most of the parking lot and the inert call boxes still standing at each space.

Maureen walked into the restaurant and looked for an open booth, suddenly conscious of the fact that she was the only person there under 60. She tried to slide furtively into a corner table and began to study the menu, aware that almost everyone in the restaurant was staring at her. She was unable to find anything truly vegetarian on the menu and tried to query the waitress about her options. After a few surly responses, Mo decided on a small salad and grilled cheese sandwich. She pulled Abbie Hoffman back out and flipped through, trying to read while she waited for her food. The feeling of sextagenarian stares on her uncombed head and sweaty face was as distracting as Pollyanna’s cheerful interventions, and when her food finally came, she ate with her head down and her cheeks angrily burning, wishing she had gone to Pizza Hut instead where she could at least get a slice of cheese pizza without being treated like communist ex-convict from Mars. She paid her bill immediately after finishing the gooey Velveeta sandwich tossed in front of her and left a 25 cent tip. Once out into the town again, the streets lined with elm trees and clapboard houses, she determined that their “liberal radar” must have failed to activate the trap door that must surely lie just outside of town, waiting to keep out radical maurauders like herself. She went straight to the gas station that served as Dixon’s bus depot and boarded the empty bus, grateful for an extra hour of quiet at last.

Twenty years ago, she might have hitchhiked her way out of town instead. Stuck out her thumb in front of a kindly cross-country semi driver, or jammed with a van full of hippies. Maybe she'd be telling her story to a nice older couple who reminded her of her grandparents--a couple who would listen politely and later, after dropping her off, be grateful that their own grandchildren where married or in school right now, not traipsing around the country aimlessly. But she had answered too many late night crisis calls, made referrals for rape counselors and emergency room treatments, to place that kind of trust in the kindness of strangers.

Maureen surveyed the 2:30 a.m. bus station. A couple of guys her age plunked quarters into portable televisions for 15 minutes at a time. A group of young black guys were animately playing pinball, shaking & slamming the machine. A few children were scattered around the terminal, sprawled over rows of seats, sleeping oblivious to their dingy, uncomfortable accomodations.

She looked down at the floor. It was unmopped, but there were no visible signs of life there. Maureen dropped her backback down into a corner and lowered herself onto the floor. Cupping her head & arms around the backpack as a pillow, she closed her eyes and immediately fell into that middle place between sleeping and waking. She felt her breathing change and the sounds of pinball and television and waking, crying babies drifted a little further away. It turned into a wallpaper of sound. Black wallpaper with dancing flowers blinking duller and brighter with decreases and increases of noise. In front of the wallpaper, she dreamed where she had been. She walked through rooms of Clark's house that led downstairs in the shelter, where children ate breakfast before school as if they were in their own homes.

The wallpaper fell, rolling itself down the walls of classrooms where she had studied Spanish and history. Clark wrote notes the wallpaper in incandescent marker, moving quickly from panel to panel, top to bottom, to fill the entire room. She watched his lips form words taht she was forgetting to hear and all she wanted to do was jump out of her desk and run over to him, but he was so busy writing that he didn't know she was there. And then a voice came into the classroom over the loudspeaker announcing "Now boarding at door 7, the 3:15 for Chicago and all points east . . . ."

The wallpaper faded to gray and then white as Maureen forced her eyes open and looked up at the fluorescent light over her head. The bus room sounds rushed back to her and she saw a small line of people--the tv watchers and a couple of the pinball players, and a young mother with two children--all with their suitcases on the floor beside them, waiting to board the bus.

Still sleepy and disappointed, she sat upright and focused her eyes on the young woman. This small family might have passed through a shelter like the one Mo was leaving. Maybe this was a midnight run away from a battering husband. The family looked a little grungy. The woman's toddler daughter flopped limply over her shoulder while the son, maybe 7 or 8, leaded against his mother trying to catch--or not to lose--a few moments of standing shut-eye.

As Maureen stood up and grabbed her backpack, heading toward the short line, she hoped that the bus wasn't already too crowded. All she wanted was a seat to herself to stretch out, without the obligations of conversation, to sleep. And maybe to re-eneter the wallpapered classroom to see how her dream might have ended.

Maureen stretched out with a book, grateful that she wouldn’t have to share a seat with anyone. She was prepared to advise potential neighbors that she had a long trip ahead of her and would want to stretch out to sleep. , which was true, despite the fact that she had no set destination. After a couple of months on the road, she was beginning to view as interlopers anyone who would be on the bus less than four hours--dilettantes of the road. As a hearty cross-country traveler, she has surely earned some stripes. Her legs stretched across both seats causing her feet to jut slightly into the aisle, a large knapsack riding shotgun, and her nose seemingly buried in a book from which she peered up furtively as people passed her seat, new passengers would stop in front of her then begin scanning the rest of the bus for more welcoming accommodations.

Comfortably dug in, Maureen moaned as the bus driver stood up beside the front luggage rack and turned on the small television sets perched throughout the bus. He popped in a videotape, informing them tha their family-friendly distraction for the next two hours would be Pollyanna.

Maureen tried to focus on the text before--a storebought copy of Steal This Book. Abbie Hoffman was, ironically, advising junior outlaws on how to get free greyhound rides by various nefarious machinations, and Mo was kicking herself for shelling out her money to the authorities for her trek. Despite her anguish over the system, though she knew she was too ernest to pull off a scam straight-faced, she convinced herself that it was just as well. There were always too many revolutionaries in jail, many, she suspected, for foolish rather than meaningful breaches of the law.

She was not anxious to waste her time and her bail money in that manner.

The television continued to draw her attention away from the manifesto before her and she could not help from staring up, mesmerized as she was repulsed. One of her favorite things about life on the road had been the lack of distractions. She could listen in on people’s conversations if she liked or stare out the window in a reverie, contemplating the long corridors of trees like a receiving line, pine trees lifting their skirts in curtsey, ballerinas skinny string bean pine trees with bird legs, olive oyl in green fur coats and tutus. But she could just as easily sleep or read or just entertain her own thoughts. She especially loved the dark quiet overnight bus trips, with the occasional small overhead lights turned in here and there in the bus, as night owls quietly read or stared into the darkness trying to make out barns and silos. But the television demanded her senses engage like an angry parent screaming for a child to pay attention or a neglected lover trying to hold onto their allure. The television screen reached out to her jaw and tipped it back each time her independent mind tried to reassert itself.

Images of Big Brother imposed themselves over the young face of Halley Mills, Stalin in a ruffled yellow dress, his flat square social-realism index finger poking in her face and informing her that despite the insistence of MTv, the counterrevolution would be televised. On the streets of the cities loud music was constantly coming out of overhead speakers on the street and in Minneapolis, Mo remembered noticing video cameras perched from atop streetlight poles. As long as you are never alone with your thoughts, unable to entertain private ideas, you will never cast off your shackles. A chicken in every pot a car in every garage and a television in every room.

Maureen intermittently set her book in her lap, her finger inserted in the book to hold her place, and picked it up again, trying to reassert her attention span. Midway into the movie she began to wonder how the name Pollyanna had gained such a bad rap. Did people really loathe the cheerful little girl more than the complacent sourpusses under the thumb of an aristocratic tyrant? Was meanness and cowardice really preferable to optimism? the bumpy bus ride was also starting to make her horny and she felt slighly blasphemous to think of sex while watching Pollyanna. She tried once more to turn her face toward the window and avoid the halogen gaze of a child who no longer existed. If she couldn’t read or think, maybe she could at least catch a short nap and ream of what might be at her next destination.

Heading west from Chicago, they were informed that there would be a long lunch layover in the next small town. Maureen craned her neck to see the approaching road signs: Dixon, Illinois. Boyhood Home of Ronald Reagan.

It had been a couple of days since she had managed a full shower, although she took sponge baths each day in whatever restaurant or bus terminal washroom was available. She felt a bit grungy, but stopping in the gas station restroom to check herself in the mirror, determined that she was still presentable to go out looking for food. She stepped into a bathroom stall to change into the fresh dress she had brought from her backpack. It was a sleeveless knit dress that fit like a t-shirt, perfect for the warm June day, with a bright yellow sunburst amid a tie-dyed milkyway.

She tucked her shorts and tshirt into the smaller bag she carried with her on stops and headed down the street, looking for a place to while away the afternoon. She passed several fast food restaurants, but kept walking, as she preferred to frequent small, family-owned restaurants, thus supporting the local economy. She found a small diner that appeared to be the remnant of an A&W, with the long davenport covering most of the parking lot and the inert call boxes still standing at each space.

Maureen walked into the restaurant and looked for an open booth, suddenly conscious of the fact that she was the only person there under 60. She tried to slide furtively into a corner table and began to study the menu, aware that almost everyone in the restaurant was staring at her. She was unable to find anything truly vegetarian on the menu and tried to query the waitress about her options. After a few surly responses, Mo decided on a small salad and grilled cheese sandwich. She pulled Abbie Hoffman back out and flipped through, trying to read while she waited for her food. The feeling of sextagenarian stares on her uncombed head and sweaty face was as distracting as Pollyanna’s cheerful interventions, and when her food finally came, she ate with her head down and her cheeks angrily burning, wishing she had gone to Pizza Hut instead where she could at least get a slice of cheese pizza without being treated like communist ex-convict from Mars. She paid her bill immediately after finishing the gooey Velveeta sandwich tossed in front of her and left a 25 cent tip. Once out into the town again, the streets lined with elm trees and clapboard houses, she determined that their “liberal radar” must have failed to activate the trap door that must surely lie just outside of town, waiting to keep out radical maurauders like herself. She went straight to the gas station that served as Dixon’s bus depot and boarded the empty bus, grateful for an extra hour of quiet at last.

Wednesday, April 03, 2013

Chapter 9 of my accursed novel

CHAPTER: DAVENPORT

The bus shifted slightly as it slowed down She turned her head toward the window and saw that they were coming into a town. At the edge of town, they passed a cemetery with a sign at the gate: Closed for the season. Call for appointments. She became taken with the notion that cemeteries closed down for the winter, the dead hibernating in grizzly bear slumber. The ground in January would become too solid, too frozen for his great grandmother's spirit to come out and greet her, Mo's shivering hands trying to offer and out-of-season bouquet, her chattering teeth and white breath floating out to meet no one.

Better still was the notion of making appointments with the dead, as if they might have had other plans. Maureen could hear her grandfather excusing himself from a ghostly poker game. "Gotta go, fellas. My granddaughter's coming to visit. Same time tomorra?"

She started to think about otehr people with whom she might make appointments. How far in advance might she need for a tryst with Jim Morrison at Pere LaChaise? Maybe she could while away part of the day with Oscar Wilde before getting a few words in with the Lizard King. Or a trip down to South America for some advice from Che Guevara or Chico Mendes.

If there was any kind of justice in the world, Chico wasn't even in these days. She hoped he was still wandering the rubber plantations, speaking encouragement, rallying the trops, and making frequent visits to his murderers. Was his spirit still debating their consciences? Did their wives' faces turn to Chico's beneath them at night, looking up and winking just before the moment of climax?

The bus hit a deep pothole and everyone was jostled. A couple of backpacks jumped the rope railing of the overhead compartments, falling into people's laps or into the aisle. The driver's staticky ghost came back through the intercom. "Sorry about that, folks. We'll be pulling into the terminal soon. For those of you travelling onward, this bus will be departing again in one hour.

Maureen looked around the city outside her window, trying to determine if this would be a good place to stay for a few days. The city looked run down, full of old factories that may or may not still make tractors or dog food or lunch meat. Maureen leaned forward and asked the young man ahead of her where they were. "I'm not sure. I'm on my way to St. Louis. Where you going?"

A young black woman across the aisle from them was standing up, pulling down a suitcase from the overhead luggage rack. She nudged her toddler. "Wake up, honey. We're almost there." The woman looked over at Maureen. "Davenport, Iowa."

The bus shifted slightly as it slowed down She turned her head toward the window and saw that they were coming into a town. At the edge of town, they passed a cemetery with a sign at the gate: Closed for the season. Call for appointments. She became taken with the notion that cemeteries closed down for the winter, the dead hibernating in grizzly bear slumber. The ground in January would become too solid, too frozen for his great grandmother's spirit to come out and greet her, Mo's shivering hands trying to offer and out-of-season bouquet, her chattering teeth and white breath floating out to meet no one.

Better still was the notion of making appointments with the dead, as if they might have had other plans. Maureen could hear her grandfather excusing himself from a ghostly poker game. "Gotta go, fellas. My granddaughter's coming to visit. Same time tomorra?"

She started to think about otehr people with whom she might make appointments. How far in advance might she need for a tryst with Jim Morrison at Pere LaChaise? Maybe she could while away part of the day with Oscar Wilde before getting a few words in with the Lizard King. Or a trip down to South America for some advice from Che Guevara or Chico Mendes.

If there was any kind of justice in the world, Chico wasn't even in these days. She hoped he was still wandering the rubber plantations, speaking encouragement, rallying the trops, and making frequent visits to his murderers. Was his spirit still debating their consciences? Did their wives' faces turn to Chico's beneath them at night, looking up and winking just before the moment of climax?

The bus hit a deep pothole and everyone was jostled. A couple of backpacks jumped the rope railing of the overhead compartments, falling into people's laps or into the aisle. The driver's staticky ghost came back through the intercom. "Sorry about that, folks. We'll be pulling into the terminal soon. For those of you travelling onward, this bus will be departing again in one hour.

Maureen looked around the city outside her window, trying to determine if this would be a good place to stay for a few days. The city looked run down, full of old factories that may or may not still make tractors or dog food or lunch meat. Maureen leaned forward and asked the young man ahead of her where they were. "I'm not sure. I'm on my way to St. Louis. Where you going?"

A young black woman across the aisle from them was standing up, pulling down a suitcase from the overhead luggage rack. She nudged her toddler. "Wake up, honey. We're almost there." The woman looked over at Maureen. "Davenport, Iowa."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)